The Psychology of Risk

Simon Morse

Security Architect, Versent

Simon Morse

Security Architect, Versent

I work in the professional arena and on a daily basis discover, analyse and make recommendations on risks that exist in organisations. But I am frequently dismayed by what I see as a skewed view of reality people have when they make decisions about risk, or even to form views on current issues in the news and their life in general.

While travelling back through Melbourne airport recently, there was a single security scanner in operation with maybe a hundred or so tired and bedraggled travelers queued up. Now I’m all for ensuring that air travel is safe, but if we as a society decide that these measures are necessary, then surely it hasn’t been managed properly. Either the original risk based decision wasn’t valid, or more resources need to be directed to make this work properly (presumably with the increased financial cost being passed on to travelers and by extension along the line to businesses and eventually customers as a result).

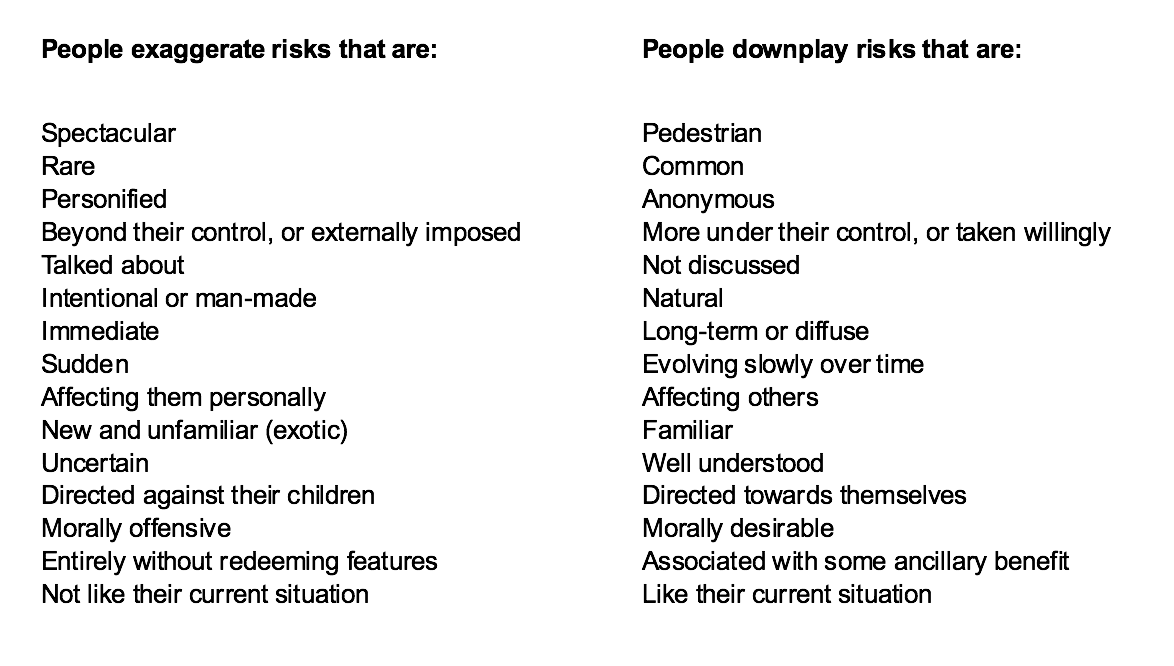

The inspiration for this article came originally from Bruce Schneier who is a long-standing contributor in the fields of cryptography, security, risk and public policy. I’d highly recommend those with a further interest in those areas to check out his blog at www.schneier.com. Here’s a great table from one of his essays that illustrate some distortions when people are evaluating risk:

You might see a bit of a pattern building up here. The first group are all what we might think of as arising from a “gut reaction”. These are the type of things that make great news stories, give rise to an unusually strong reaction and are often more emotional reactions than clear headed evaluation of the facts. Similarly, events in the second group tend to be downplayed due to the lack of these types of gut reactions coming to the fore.

The best theory that I’ve heard on this phenomenon relates to the areas of our brain that process risk. The “primitive” amygdala is the area at the base of our brain at the back and is common to most members of the animal kingdom. This is where we get adrenaline from – and as a result get angry, get fearful or get defensive. What sets us apart as Homo Sapiens is our remarkable ability to lift ourselves above these basic instincts. Unlike almost all other animals, we do have the ability to think clearly and to evaluate risk. This needs to be a conscious choice or habit, and for most of us, is hard work. But we can do it.

You can understand why the amygdala “works” for a plains roaming creature, and depending on your views on evolution, our ancestors as well. Let’s take a representative primate – Jake the monkey. Life is pretty precarious and pretty drastic action is frequently needed – to escape from a predator, bag a mate, steal food from his fellows in the troupe etc. Gut reactions work for Jake because there actually is an approximate correlation between how important an event is to him and the strength of his reactions. He very rarely sees a Lion that often, but when he does, he really does need for his adrenaline to kick in and get out of there.

But here’s the problem, our amygdala is still operating for us “higher” creatures and especially in modern times, we are flooding it with input. Partly, in our quest to avoid boredom we may read a thriller, listen to evocative music, flirt, play sport and, perhaps most importantly for this primitive part of the brain, watch spectacular and emotion provoking visual content, soaking it up to get our emotional high. This can be fine for our sense of escapism and entertainment, but unfortunately it is also exactly the same approach that the media adopts when presenting the news. Boring events don’t make the news, as I mentioned above, it’s the stuff in the first column that makes the cut. As a result, our world is not like Jakes’. The correlation between events that are relevant to our life, and the strength of our reactions have broken down. We are more likely to see spectacular events because they are more spectacular, not because they are more common. In fact, if they become common, then they lose the “sense of the other” that make them newsworthy. Issues such as road accidents and cancer take the lives of many of our citizens on a heartbreakingly regular basis, but we often are focussed on mitigating risks relating to the spectacular, like my line up to eliminate the (theoretically) imminent ISIS attack on the 5:30 Melbourne to Sydney haul.

I don’t have any pat answers for you as to what to do about issue X or Y, because as I mentioned above, sitting down and analysing risk is hard work. But, the first step in solving the problem is to recognise it. At Versent, we make sure to approach risk as we do with all of our other practices. Decision making is predictable, traceable, automated wherever possible, and scientific rather than based on gutfeel. We make sure that we give proper weighting to those unspectacular concerns that will never make the media, gossip sessions, or bar room discussions.

As business and technology decision makers, and as members of the community, we are frequently evaluating risk – what level of insurance should I take out, where do I live, how much debt can I carry and be comfortable. It’s vital that you don’t get caught up in emotion, but sit down and think clearly about the issues. And from time to time when you find your blood pressure rising and you are offended or overly passionate about sport, politics, or religion as we inevitably will be – stop, take a breath and dial down the emotion and see if makes a difference. Here’s to a life well analysed…